This week, the Cuban Ministry of Public Health (MINSAP) used an extensive piece in Cubadebate to present its official stance on the severe medicine shortage affecting the nation.

Under the headline "Control and Oversight: MINSAP's Response to the Illegal Drug Market," health authorities pinned the blame on the U.S. embargo and global financial challenges for the current scarcity. However, they sidestepped acknowledging the significant management failures that have pushed the national pharmaceutical system to the edge of collapse.

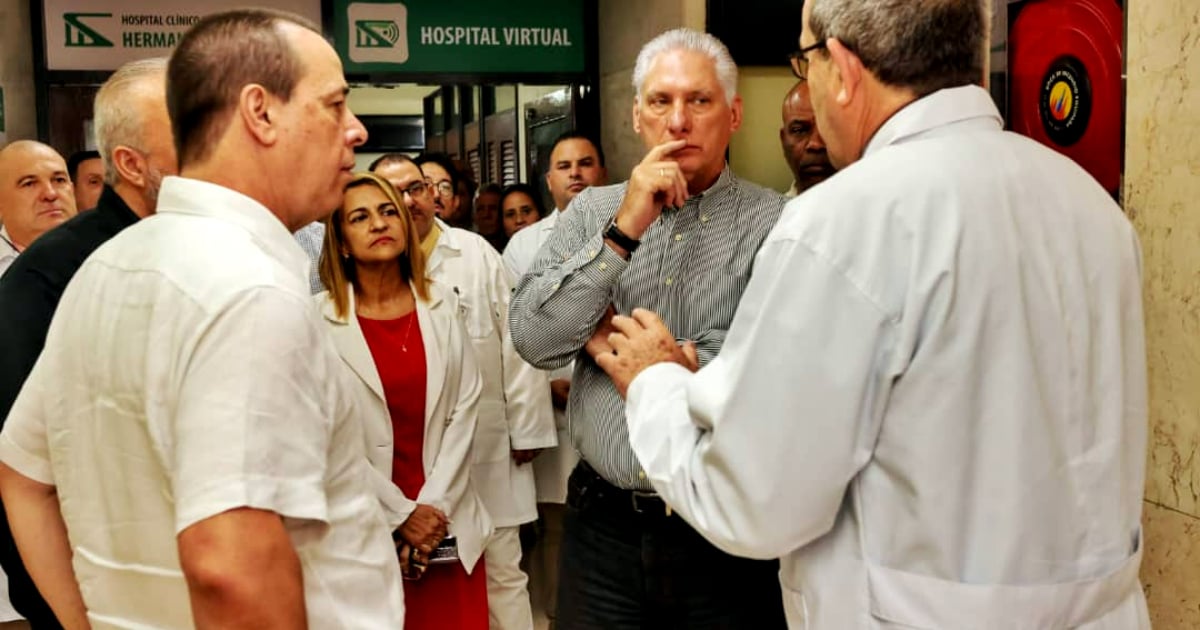

The article, written by pro-government journalist Frank Martínez Rivero, included statements from Cristina Lara Bastanzuri, Director of Medicines and Medical Technologies, and Maylin Beltrán Delgado, Head of the Department of Pharmacies and Optics.

A Partial Diagnosis for a Total Crisis The officials admitted to a "practically total shortage" in community pharmacy networks, failing even to ensure regular distribution of controlled drugs to chronic patients. Yet, their analysis was incomplete: they almost entirely attributed the situation to the U.S. economic and financial blockade, ignoring internal causes that have decayed the system over the years.

According to MINSAP, Cuba's pharmaceutical industry has lost production capacity due to funding shortages, the withdrawal of suppliers, and banking difficulties in making international payments. While these issues exist and complicate operations, the authorities failed to mention that Cuba has outstanding debts with countries like India, China, and Spain. Nor did they address endemic issues like technological obsolescence and corruption within BioCubaFarma, which are independent of Washington's actions.

The official narrative also omitted issues like industrial maintenance neglect, logistical inefficiencies, or the absolute centralization that prevents the private sector from legally importing or manufacturing medicines. Instead of announcing a feasible production or international cooperation plan, MINSAP's "institutional response" focused on police monitoring and control. The officials boasted of conducting over 5,000 pharmacy inspections and maintaining close coordination with the Ministry of the Interior (MININT) to combat illegal drug sales.

Out of the 33 "extraordinary incidents" identified, 18 were pharmacy thefts, while others involved healthcare workers. However, the ministry treated these as isolated crimes, ignoring that the black market is a direct result of shortages and the lack of official transparency. They also sought to deter the public from resorting to drugs imported by travelers or bought in informal networks, warning of health and legal risks.

MINSAP cautioned that those reselling controlled medications could face drug trafficking charges, a measure seemingly more aimed at criminalizing daily survival than providing real solutions for those unable to find medicines in the state network. Another part of the Cubadebate article attempted to frame stopgap measures as achievements: the clinic-based sales system, rotating shifts to avoid queues, the promotion of natural medicine, and the expansion of e-commerce in selected pharmacies.

Nevertheless, none of these initiatives address the structural issue: the lack of essential medicines and the state's inability to ensure a stable minimum supply. In recent years, shortages have worsened to unprecedented levels. Sources within the sector estimate that over 70% of the basic medication list is unavailable, with restocking cycles extending from 12-15 days to 60 days or more.

This situation has driven thousands of Cubans to the informal market, where prices are tenfold, leaving chronic patients without regular access to vital treatments. The official version published by Cubadebate confirms what the population experiences daily: a prolonged health crisis that the government attempts to justify with the embargo while avoiding any self-criticism of its state management model.

MINSAP acknowledges the symptoms but not the causes. Rather than restructuring the system, diversifying suppliers, or allowing private sector participation, it prefers to strengthen police and administrative controls that merely mask the collapse. The outcome is a healthcare system that can no longer guarantee even the most basic medicines. Meanwhile, the regime clings to talk of "pharmaceutical sovereignty," when in reality, dependency, debt, and inefficiency have left Cubans without pills, alternatives, or hope.

The Absent Minister: José Ángel Portal Miranda and Unclaimed Responsibility The prolonged health and pharmaceutical crisis in Cuba has identifiable figures and accountability. Leading MINSAP since 2018, José Ángel Portal Miranda has remained in the background during the worst months of the system's collapse, avoiding public explanations and sending his subordinates to face social discontent.

His media absence has become a symbol of opaque and failed management, unable to offer transparency or real solutions to a population increasingly desperate for medicine or basic medical care. Since the current shortage cycle began, Portal Miranda has limited himself to bureaucratic speeches or propaganda messages about "institutional efforts," while directors and department heads appear in state media to justify the absence of medications, the loss of suppliers, or the rise of the black market.

These officials echo the embargo argument and financial difficulties, yet the minister, the political and executive leader of the system, remains hidden, failing to provide clear figures or acknowledge internal errors. His silence is even more glaring considering his role during other recent crises. In October, Portal Miranda downplayed an epidemic outbreak in Matanzas and denied related deaths, despite local reports and citizen complaints proving otherwise.

A month later, the regime partially admitted responsibility for the national epidemiological crisis, but the minister again absented himself from informational and accountability spaces. Official MINSAP publications repeat mantras of resistance and sovereignty but avoid any self-critique. Meanwhile, hospital deterioration, medication shortages, and public distrust grow daily.

In this context, Portal Miranda has lost legitimacy even among sector workers, who accuse him of leading a directionless ministry and concealing the severity of real data. The Cuban healthcare system crisis can no longer be explained solely by the embargo or lack of external funding. It is also — and above all — the direct result of inefficient, authoritarian, and silent governmental management, led in Public Health by an official who refuses to be accountable to the country suffering the consequences of his incompetence.

The Cuban Pharmaceutical Crisis

What are the main causes of the pharmaceutical crisis in Cuba?

The crisis is attributed to several factors, including the U.S. embargo, lack of funding, withdrawal of suppliers, and banking challenges. However, internal issues such as technological obsolescence, corruption, and centralized management also play significant roles.

How has the Cuban government responded to the medicine shortage?

The government's response has focused on police monitoring and control, conducting inspections, and warning against using imported or informally bought drugs. However, it has not addressed the structural issues causing the shortages.

What impact has the crisis had on the Cuban population?

The crisis has forced many Cubans into the informal market, where drug prices are significantly higher, and has left chronic patients without regular access to necessary treatments.