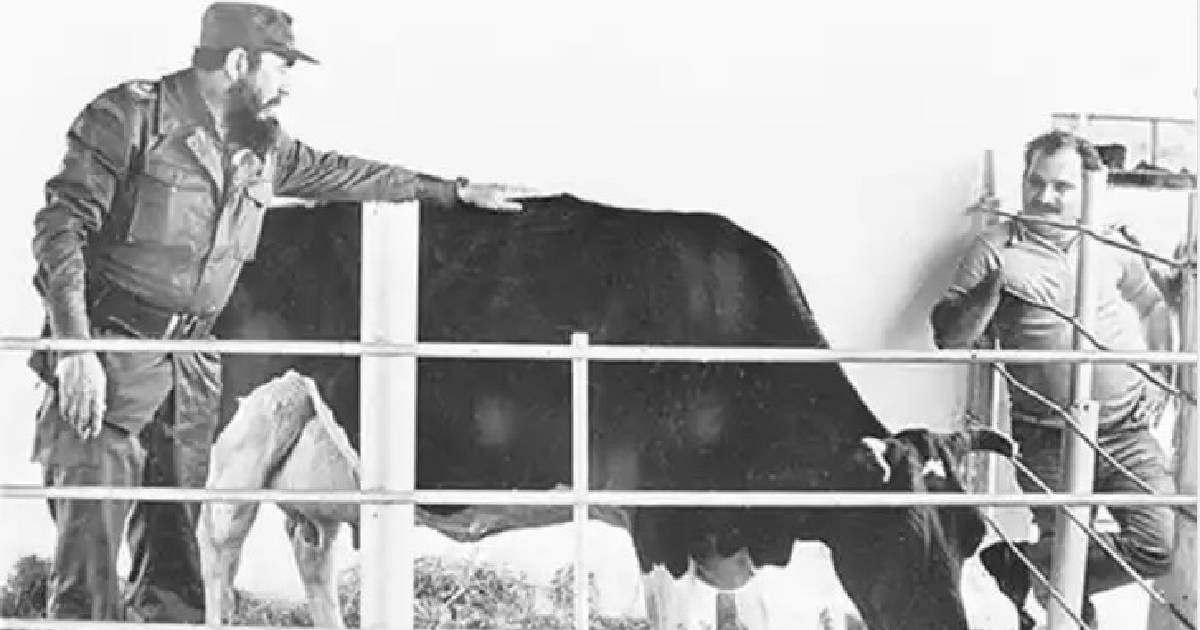

Dr. Ernesto Medina Álvarez, who dedicated decades to the cattle industry in Villa Clara, recently stated that the sector remains "indebted" to Fidel Castro (1926-2016). He credited Castro as the primary advocate for the development of cattle farming in Cuba, despite the country's ongoing struggle to achieve self-sufficiency in milk and meat for over fifty years.

As a former provincial president of the Cuban Association of Animal Production, Medina highlighted various initiatives launched under Castro's leadership. These included a network of insemination centers, genetic companies, and the utilization of industrial waste for cattle feed.

During an interview with radio station CMHW, Medina emphasized that with adequate supplies and technology, state-run cattle farming was "efficient." He referenced production figures from 1987, noting that companies like La Vitrina and Remedios in Villa Clara exceeded 17 and 11 million liters of milk annually, respectively.

Medina recalled a visit from Uruguayan technicians sent by former President José Mujica (1935-2025), who praised the infrastructure established by Castro but criticized Cuban ranchers for not fully utilizing it.

The Shift to Private Hands

Today, much of Cuba's cattle industry is in private hands, with producers owning only a few cattle, hindering the implementation of scientific methods, technology, and insemination programs. Medina argued that "it shouldn't be that this is the only agricultural branch with more penalties than benefits. If you don't register a birth, you're fined; if you don't report theft or slaughter, you're fined, etc. What I'm saying is that cattle farming needs more support and resources."

He also noted that Cuba needs more cattle farmers, not just "animal holders," as is currently the case. Medina called for a change that would allow exports and enable producers to earn foreign currency to purchase resources, taking cues from Latin American models.

Failed Past Projects

Medina suggested revisiting the cultivation of protein-rich plants like moringa, mulberry, and tithonia, which Castro had demonstrated to be effective. He warned that natural pasture protein is insufficient and that sugarcane, with just 3% protein, merely prevents cattle from dying but does not promote their growth.

His comments contrast with the history of failed cattle projects under Castro, from the famous Ubre Blanca to plans like Voisin Rational Grazing or the massive cultivation of "Pangola," which failed to turn Cuba into a dairy powerhouse. The goal of surpassing the Netherlands and France by 1970 with eight million cows and 30 million liters of milk daily never materialized.

Current Crisis in the Cattle Industry

Cuba's cattle industry is in severe crisis, having lost over 900,000 head of cattle since 2019, according to official data released by the Ministry of Agriculture (MINAG) in July during the Fifth Ordinary Period of Sessions of the National Assembly of People's Power.

Arián Gutiérrez Velázquez, the General Director of Cattle, reported that by the end of 2024, the cattle population was only three million, a decline of nearly 400,000 from the previous year. This downward trend is not only due to natural factors like mortality but also significant structural issues, including theft and illegal slaughter, which affected over 27,000 animals, including cattle and horses, last year alone.

In 1956, Cuba had a population of 6,676,000 people. The Zebu breed dominated Cuban pastures, with six million cattle, equating to roughly 0.90 cattle per person. This did not include smaller livestock, which totaled 4,280,000, comprising 500,000 horses, 3.4 million pigs, and 200,000 sheep, among others.

Decline in Milk Production

Recently, the state-run newspaper Granma acknowledged that Camagüey's annual milk production had fallen to less than half of the 92 million liters reached in 2019, with only 41.1 million liters collected in 2024.

"Last year, due to theft, slaughter, and other causes, we lost as many cows as there are in a municipality. If this trend continues, in about 15 years, there will be no cattle industry in Camagüey, and much less milk," the newspaper warned.

All indications suggest that 2025 will end with a deficit of over a million liters compared to both the annual plan and 2024, in a province once considered Cuba's primary dairy region.

Since late 2023, Cuba's dairy industry has shown clear signs of structural collapse. In November, the then-Minister of the Food Industry admitted that the country did not have enough milk for the entire population and aimed to provide "a portion" to the most vulnerable groups, an unprecedented acknowledgment of the state's limitations in ensuring an essential product.

In a 2007 speech as acting head of state, Raúl Castro criticized that Cubans only received milk until the age of seven and insisted that needed to change. However, he left the Council of State in 2021 without altering this grim reality. Eighteen years after his promise, the situation remains unchanged, with families raising their children without this and other essential foods.

Today, as the country imports much of the food it once produced, the most visible debt isn't to the late leader, but to the Cuban people's tables, which remain devoid of the products that decades of experimentation and centralized planning never managed to secure.

Understanding Cuba's Cattle Industry Challenges

Why is Cuba's cattle industry struggling?

Cuba's cattle industry faces issues such as a declining cattle population, theft, illegal slaughter, and insufficient resources and technology. These challenges have been exacerbated by structural problems and a lack of effective governmental support.

What historical projects failed to improve Cuba's dairy production?

Projects like Ubre Blanca, Voisin Rational Grazing, and the cultivation of "Pangola" grass failed to transform Cuba into a dairy powerhouse. Despite ambitious goals, these initiatives did not result in the anticipated growth in milk production.

What changes are suggested to improve the cattle industry in Cuba?

Suggestions include increasing support and resources for cattle farmers, revisiting the cultivation of protein-rich plants, and enabling exports to earn foreign currency for purchasing necessary resources.