Following a prolonged shortage, "free" bread has made its way back to the Isle of Youth. However, this comeback does little to ease the financial burden on families. Priced at 110 pesos for a soft-crusted 200-gram loaf, the bread reaches consumers through micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), driving up its final cost due to the purchase of flour and sugar through these channels.

Alberto Mirabal, head of the Food Company, confirmed that the 48 tons of wheat flour currently available were procured from the private sector. This procurement explains the price difference compared to the Cuban Bread Chain. "In our case, unlike the Bread Chain which receives flour through government channels, we have to buy it, along with the sugar used in bread production, from MSMEs to provide this 'free' bread to the people," Mirabal stated, as reported by the official newspaper Victoria.

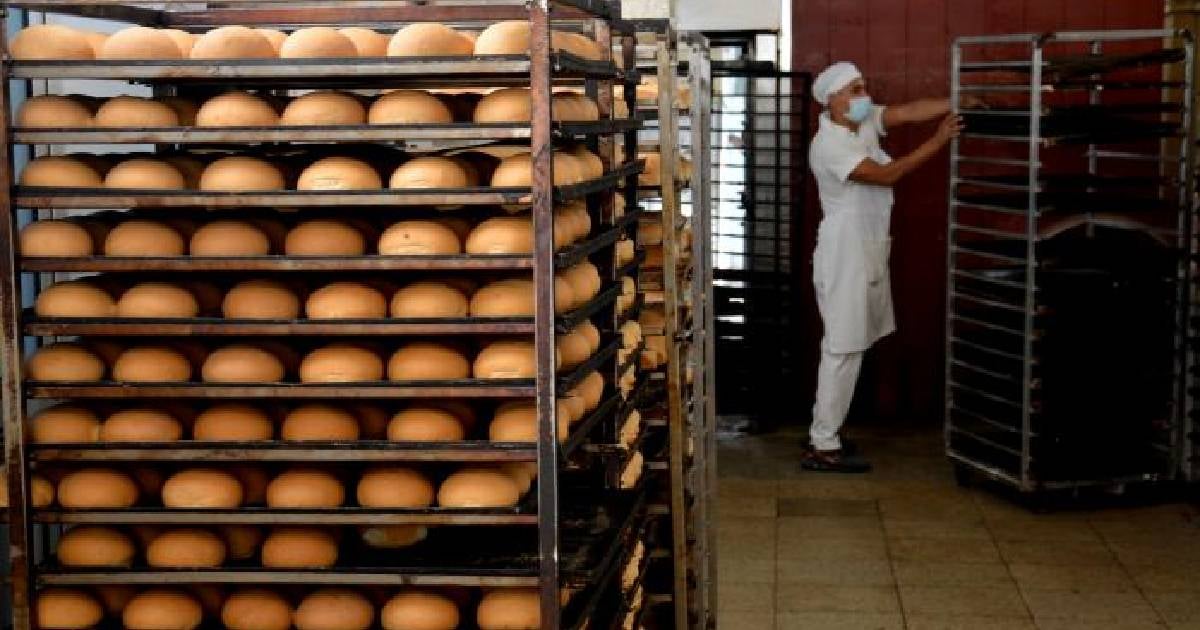

The quantities produced are insufficient to meet the demand. Bakeries have been instructed to produce between 180 and 300 pieces per day, with distribution based on the length of the line: two per person if there are many people, more if the crowd is smaller. This plan merely manages scarcity rather than addressing the need.

Structural Changes and Economic Implications

Adding to the complexity is a structural shift that further complicates matters. The Cuban Bread Chain is set to be dissolved and absorbed by the Food Company. According to Ever Borges, the current director of the Bread Chain in the Isle of Youth, several bakeries will transform into state-run MSMEs, while others will support the Food Company by contributing to the basic rationed bread supply.

"We are waiting for the directors to arrive in the municipality to implement the transfer. Once completed, we'll create the state-run MSME project, and we’ll have to purchase everything from MSMEs where we know products are expensive. We'll be making cookies, breadsticks, and various bread at slightly higher prices," Borges explained.

The Cost of "Free" Bread

Under the new model, pastry and other derivative products will also depend on MSME contracts, a process still underway. Official promises indicate that the units located in Paseo Martí in Nueva Gerona and the park in the town of La Fe will maintain production from Monday to Saturday during the summer.

"We'll be offering bread at 100 pesos and will look for cost-effective options to provide more affordable bread for those who can't afford the 100-peso loaf," added the director. Ultimately, everything relies on costs and the market, not on a public policy focused on nutritional welfare.

The reintroduction of "free" bread doesn't address the core issues: high prices, limited supply, and a fragile food system now driven by a "survival of the fittest" mentality. Instead of ensuring a staple food, authorities seem content with providing bread... for the few.

Regional Price Disparities

The National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI) reported that in April, the price of an unrationed soft round bread (80 grams) reached 60 Cuban pesos (CUP) in Santiago de Cuba, the highest in the country that month. The lowest price was 18 CUP in Ciego de Ávila, highlighting significant regional disparities in access to this essential food.

In Havana, prices ranged from 21.42 to 58.33 CUP per unit, making it one of the provinces with the greatest internal price variation. Matanzas was the only province to report a single price of 39 pesos, without variations, while Cienfuegos and Villa Clara recorded maximum values above 50 CUP. Provinces like Guantánamo, Holguín, and Las Tunas showed more contained prices, although still high relative to average wages.

The wheat flour shortage in Cuba has forced restrictions on the production and distribution of rationed bread in several provinces. In Artemisa, for instance, rationed bread is sold only on alternate days and includes "innovative" blends of sweet potato, cassava, and pumpkin to stretch the limited resources. In Guantánamo, rationed bread distribution is limited to children under 13 and social institutions, while "free" bread has significantly increased in price.

Cienfuegos implemented new prices reaching up to 150 CUP for a 200-gram loaf, responding to rising production costs. In Santiago de Cuba, where ONEI recorded the national maximum price, there were public complaints in March about bread being sold for up to 50 CUP, leading to public outcry over market speculation and lack of state regulation.

Understanding Cuba's Bread Crisis

What factors contribute to the high price of bread on the Isle of Youth?

The high price of bread is due to the need to purchase flour and sugar through MSMEs, which increases production costs. This is compounded by the lack of government-supplied ingredients, forcing the use of private sector resources.

How does the new model affect bread production and pricing?

Under the new model, bakeries will transform into state-run MSMEs, requiring them to purchase supplies at market rates, which are higher. This shift leads to increased bread prices and a dependency on the ability to contract with MSMEs.

What are the regional disparities in bread pricing across Cuba?

Bread prices vary significantly across Cuba, with Santiago de Cuba recording the highest prices in April. Factors such as regional supply, local economic conditions, and access to ingredients contribute to these disparities.